By Foster Obi

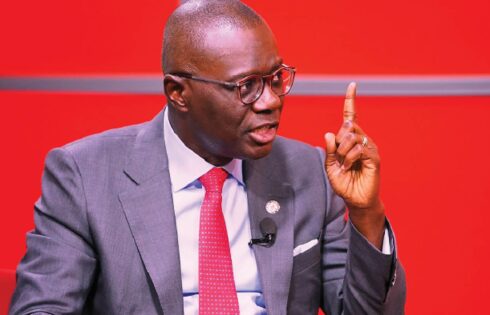

The maritime community in Nigeria has erupted in a chorus of condemnation following a statement attributed to Lagos State Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu, decrying the Nigerian Ports Authority (NPA)’s efforts to deepen and operationalise ports in the South-South and South-East, including Warri Port Complex, Onne Port Complex and Calabar Port as part of broader plans to ease chronic congestion in Lagos.

The League of Maritime Editors (LOME), led by its President, Mrs Remi Itie, and Secretary-General, Mr Felix Kumuyi, described the governor’s remarks as “a demonstration of obsession with Lagos dominance” and a direct affront to the notion of equitable national development. As the League puts it: “Nigeria is a federation, not a fiefdom.”

Their critique underscores two decades of over-concentration in the port sector, mainly at the country’s two major Lagos ports, Apapa Port and Tin Can Island Port which have long borne the brunt of traffic congestion, corruption, inefficiency and incessant gridlock. According to LOME, efforts to bolster and diversify port operations across Nigeria are not only justified, they are imperative.

“To now resist the decentralisation of port operations to Warri, Onne or Calabar is to insist that Nigeria’s economy remain shackled to Lagos’ dysfunction,” the League argued.

The criticism from LOME aligns with growing frustration among shipping professionals and freight operators. It comes amid a flurry of remarks by Lagos officials rejecting NPA’s decision to shift focus from Lagos to other ports.

A senior aide to the governor, Adekoya Hassan, the Senior Special Assistant on Transportation and Logistics told reporters that the “problem lies not in Lagos ports themselves but in long-standing policy flaws within NPA.” He argued that reckless attempts to divert cargo to Warri amount to a “band-aid” that ignores the real sources of inefficiency: toll-points, a malfunctioning e-call-up system, favouritism, racketeering and abuse of power by senior officials.

According to Hassan, if NPA reformed its institutional framework and aligned with modern economic realities, congestion at Apapa could be drastically reduced, making the pivot to Warri unnecessary.

Yet, many maritime stakeholders vehemently disagree with the Lagos Government’s stance. Among them is the aide to the governor of Delta State, Ossai Success, who described the opposition to the shift as “disappointing.” He insisted the decision to revive Warri and by extension reduce reliance on Lagos is in the best interest of Nigeria, arguing it would spur regional economic development, reduce logistics costs for businesses, ease congestion in Lagos and improve security and surveillance across ports.

Meanwhile, the NPA itself and other proponents of maritime reform have pointed to concrete progress at previously moribund ports. In a recent working tour of the Delta ports, the NPA Chairman and board members disclosed ongoing investments in dredging, channel maintenance, and infrastructure upgrades at Warri, Onne and Calabar, with pledges to continue modernisation across the maritime sector.

These developments are seen not as “band-aids,” but as urgent corrective measures meant to rebalance port operations, relieve Lagos of unsustainable load, and provide the country with a resilient, multipolar maritime network.

Beyond institutional voices, several merchants, truckers and citizens, many of whom spoke anonymously for fear of reprisal dismissed the Lagos State Government’s claim to be the engine of national commerce.

An influential trucker at Apapa, who asked to remain unnamed, said: “We spend days waiting at every checkpoint, paying bribes, even when our call-up number shows green. If Warri or Onne are functioning properly, why should I continue suffering here?”

An Eastern-based importer noted: “When you have to bring cargo from abroad and it’s easier to discharge in Lagos, thousands of naira are wasted on transport, demurrage and extortion. A working port in Warri or Calabar means lower cost not just for me, but for every Nigerian buying imported goods.”

Patrick Ige, a Lagos resident living near the port corridor said the perennial gridlock had become a public safety and environmental hazard: “Trucks parked for hours, sometimes overnight. Noise. Pollution. Accidents. We’ve written to the State, but the only answer is more promises, not solutions.”

Viewed in the full context of Nigeria’s maritime and economic realities, the Lagos Government’s position now appears less like a defence of competence and more like a bid to preserve economic monopoly. Several factors underscore this critique:Persistent failure to resolve Apapa gridlock despite years of state-infrastructure investments and repeated assurances of improvement. Even as late as November 2025, the State still points to “policy flaws at NPA” as root causes.

Pointing to decentralization as a “distraction” or “band-aid,” while ignoring decades of centralised congestion, corruption, and inefficiency.

Ignoring regional equity, economic justice, and the potential for national integration, by resisting the development of other viable ports, especially in the South-South and South-East.

Pitting Lagos’ narrow local interest against Nigeria’s broader national good. In effect, Sanwo-Olu’s rhetoric betrays a dangerous vision where one state monopolises commerce and sidelines other regions, a notion incompatible with genuine federalism and balanced national growth.

Analysts posit that the efforts by the NPA to revive and deepen operations at Warri, Onne, Calabar, and other ports should not be viewed as a threat to Lagos but as a strategic necessity for the whole country. They believe that resistance from Lagos, cloaked in complaints about “policy flaws,” is increasingly revealed as resistance to reform.

Picture: Lagos State Governor, Babajide Sanwo-Olu