By Foster Obi

Nigeria’s recent IMO Council Category C historic victory is cause for celebration, but it also amplifies a long-standing national embarrassment. Despite repeated promises, committees, and ministerial assurances, Nigeria still lacks a functional national shipping line.

Recall that Nigeria had a national carrier which collapsed due to corruption and official complicity.

That absence has tangible costs and strategic consequences for the country’s trade, balance of payments, and maritime independence.

The Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL) was established by the Nigerian government in 1959. Despite heavy investment and subsidies, the state-owned company was unable to compete with European lines. Much of the investment went to enriching the political elite. Deeply indebted, the NNSL was liquidated in 1995 and all 21 of its vessels were sold.

Official promises and the silence that followed:

When Adegboyega Oyetola, the Minister of Marine and Blue Economy, outlined the administration’s blue-economy agenda, he repeatedly framed indigenous shipping as central to the plan. The Ministry has published a series of statements affirming the government’s commitment: “Our commitment to indigenous shipping is total and irreversible,” the Minister is quoted as saying in an official release tied to NIMAREX activities.

Also in his earliest stakeholder engagements, the minister publicly announced plans to re-establish a national shipping line under a strategic public–private partnership, describing the initiative as capable of adding as much as $10 billion in economic value if properly structured.

Yet industry sources and insiders say the high-level promises have not translated into an actionable, funded implementation plan that would actually put government-backed tonnage to sea.

“We heard the pledges. We saw the statements. But there has been no visible pilot project, no transparent procurement or clear funding window that demonstrates those words will become ships,” said a senior maritime agency source who has attended Ministry meetings

A bitter cycle of committees, study-tours, and abandoned recommendations:

This pattern is painfully familiar. In 2016, then-Transport Minister Rotimi Amaechi received a committee report on reviving the national shipping line after the ministerial committee’s work and trips abroad. Press coverage at the time recorded concerns about patronage of foreign ships, including a widely reported figure that Nigeria was losing billions to foreign shipowners, and the committee’s recommendations were not fully implemented.

Former President of the Ship Owners Association of Nigeria, SOAN, and Chairman of Starzs Shipping Company, Chief Greg Ogbeifun, told Thisday in an interview that Nigeria was losing over $15 billion annually for not having a national shipping line, with freight services alone accounting for $7 billion.

He said this figure also reflects the taxes Nigeria is forfeiting by not employing Nigerian seafarers and other maritime professionals.

He recalled efforts by the then Minister of Transportation, Rotimi Amaechi, to revive the country’s national shipping line.

“One of the first things the Minister of Transportation, Rotimi Amaechi, did when he assumed office was to form two committees: one to work on the establishment of a national fleet, and the other to examine the structure of NIMASA,” Ogbeifun said.

As a member of the committee on the national fleet, Ogbeifun explained that their mandate was to study what other countries were doing that enables them to successfully establish and maintain their own national fleets.

Another member of that committee said the exercise produced recommendations on financing models, governance, and vessel acquisition but the report gathered dust while money was spent on foreign visits and short-term public relations.

“We travelled, we consulted, we prepared a blueprint. It was never used as the basis for a viable national fleet.”

The economic cost: valuations and official projections

Estimates cited in past reporting show the scale of the leakage. Press reporting around earlier revival efforts quoted figures such as $10 to $12 billion lost to patronage of foreign ships in specific years and government sources have put the upside from a successful national carrier in the billions. In public statements and press briefings, the Federal Government has repeatedly said a national carrier could unlock substantial value, jobs, and retention of foreign exchange.

Clarion Shipping: an indigenous start but has limits

In the vacuum left by the absence of an officially backed national fleet, private initiative has started to fill gaps. Clarion Shipping West Africa, owned by a woman has publicly launched a container service and acquired at least one indigenous-flagged containership (MV Ocean Dragon), pitching itself as Nigeria’s first fully indigenous containership operator. The firm’s launch and vessel acquisition were reported in multiple outlets earlier this year.

Clarion’s management has publicly called for patronage and policy support, highlighting challenges such as dollar-denominated port charges and the capital intensity of liner operations. Analysts and business reports note that Clarion’s arrival is an important symbol and commercially, but that a single private line cannot substitute for a deliberate state framework that addresses finance, levies, guarantees, and route support.

“Clarion’s MV Ocean Dragon shows Nigeria can own and operate ocean-going tonnage. But shipping is a long-haul, capital-intensive game. The Government must reduce structural barriers if indigenous lines are to survive,” said Kalu Eke a freight forwarder at Lagos port.

Why the Minister must move from rhetoric to delivery:

Winning a Category C seat at the IMO gives Nigeria influence in rule-making and technical decisions. But influence without capacity is hollow. A properly structured national shipping programme would: Retain freight earnings and reduce outflows of foreign exchange, Provide commercial capacity for crude, refined product, and specialist cargoes when national interest demands it, Strengthen the hand of Nigerian delegations in multilateral forums by pairing diplomacy with demonstrable capacity.

Also, it will expand training and career paths for Nigerian seafarers and shore staff, and encourage the development of local ship-management, repair, and maritime services.

It’s so humiliating that the country churns out cadets from its maritime academies yearly with no practical sea time experience.

Minister Oyetola himself has repeatedly framed the marine and blue economy as central to economic diversification and insisted indigenous shipping is a priority; words the Ministry has put on record. The sector’s question now is simple: will those words be matched by a funded implementation plan, transparent PPP terms, and early demonstrable steps such as vessel guarantees, subsidy-for-route trials, or a government anchor equity stake that draws private capital?

“The Ministry must stop issuing speeches and start publishing project documents: tender timelines, public-private governance structures, and a rolling five-year financing plan that shows how ships will actually be bought, insured, and deployed,” said Helen Udi, an international shipping policy expert.

What success would look like:

Publish a transparent PPP prospectus and procurement timeline, create a modest pilot fleet (2–4 modern multipurpose/feeder vessels) on strategic routes with guaranteed volume support, offer temporary, targeted levy relief or dollar-charging reform for newly-flagged indigenous services to fix the port-levy cash-flow mismatch like Clarion, others cite.

Use the IMO Category C seat strategically, Pair diplomatic credibility with demonstrable capacity creation on the water, Make the 2016 committee’s (and any later) recommendations public, and explain which will be adopted or discarded and why.

Nigeria’s return to the IMO Category C table should be something to ginger us. The country has both private actors (like Clarion) and a newly invigorated Ministry that has publicly vowed to back indigenous shipping. But unless the Minister moves beyond statements to publishable, funded, and accountable action plans, Nigeria risks repeating old patterns: committees, foreign trips, press releases, and no national carrier.

As Minister Oyetola put it in Ministry statements, “Our commitment to indigenous shipping is total and irreversible. Stakeholders will judge those words at the end whether they were real actions or mere words designed to hug newspaper headlines as Nigerian politicians are wont.

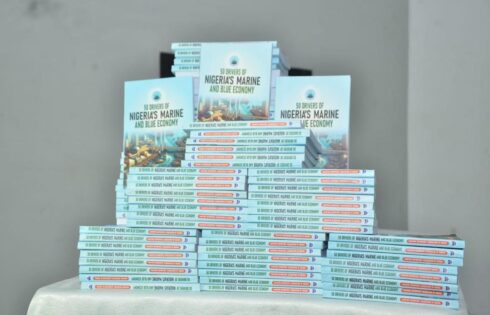

Picture: Vessels belonging to liquidated

Picture: Dr. Boniface Okechukwu Aniebonam (Ozo Ebubechukwu Umuawulu, Eze-Oba Nri

Picture: Dr. Boniface Okechukwu Aniebonam (Ozo Ebubechukwu Umuawulu, Eze-Oba Nri